|

| Figure 1. The iOS code exhibiting the SSL handshaking problem. |

As a veteran of the application development industry, I can share plenty of horror stories about things that just "went wrong," from a tape backup software vendor not having a backup of my hard drive and then having the hard drive fail after I left, to projects that were canned after being in development for four years without a single beta release.

During those 18 years, however, I can recall having to go through a very rigorous process while working on Wall Street whenever any code was considered a Release Candidate for production. Essentially, any code to be rolled out to production had to pass a code review by your peers, and we all took delight in shooting down other members' code, all in the name of quality. In one instance, a library of common routines that I created after refactoring a few of my own applications was stuck in repeated reviews for six months before it was finally approved (after many adjustments on my part).

So, it's with this hindsight that I look at the gaffe by Apple where SSL handshaking wasn't being properly validated (that ultimately resulted in iOS 7.0.6 being released during the end of February), and I marvel that this even happened in the first place. Essentially, a superfluous "goto" statement was left in the code, causing it to exit out of the validation routine prematurely. The code in question is shown in Figure 1 (taken from the Wired UK article with indentation reformatted to better fit here).

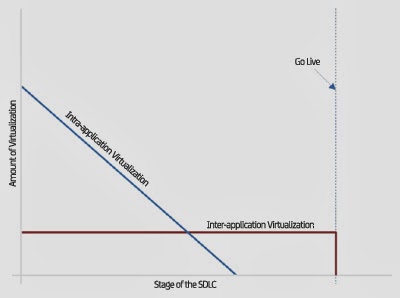

Although static code analysis tools such as HP Fortify and CAST should have caught this immediately, this lends itself to a discussion on why establishing a discipline such as Service Virtualization is so important. It has been discussed repeatedly how virtualization decreases as the software progresses to the right of the SDLC (i.e. closer to a production release), but things are slightly different in reality as illustrated in Figure 2.

Intra-application virtualization is the exercise of developing virtual services for components that exist within your own application. This occurs because components upon which a developer is dependent do not exist due to code development prioritization that is based upon the priority of the underlying business requirements. However, these availability constraints eventually work themselves out and, as a result, the need to virtualize those other components is reduced to zero at some point.

|

| Figure 2. The two types of virtualization |

(I realize these statements about the length of usage of virtualized services is not entirely accurate because there are legitimate situations where the end of virtualization may be extended or contracted.)

Regardless of the type of virtualization being used at any given time, virtual services are developed based on the flow of data between components as part of one or more transactions. This flow of data is independent of the code in that it is frequently "designed" in advance of any code being written. As a result, the data reflects the desired end state of the application or, to put it another way, what would be observed "on the wire" if the code were 100 percent correct.

Furthermore, because virtual services are essentially data and little more than data, the set of responses that can be returned by a virtual service in response to any given transaction is fully within the control of the owner of those virtual services. This allows the consumer to more easily test negative cases such as boundary conditions, off by one errors, etc.

This brings us back to the Apple problem. As you know, SSL is a technology that is used to facilitate secure communications between multiple software entities. And while both endpoints could be within the same application, more frequently it is used in inter-application communication.

The point is that virtual services could have easily participated in the SSL handshaking instead of live code. (More importantly, that inter-application virtualization would have existed a lot longer during the SDLC as noted in Figure 2.) And, since virtual services are just data that can be modified to setup specific testing scenarios, it would have been trivial to reproduce the condition that resulted in the premature exit of the handshaking code in iOS 7.